It’s Sunday afternoon in a community hall in Lille, northern France, where about 10 people gather for a theater rehearsal. Most of these amateur actors met not through the arts but in the “gilets jaunes” or yellow vests protests that peaked in 2018–19, when demonstrators in high-visibility vests blocked streets to protest fuel tax hikes and rising living costs.

The movement has since waned from its peak, though local actions continue. Still, many participants remember the solidarity and anger it produced. Sixty-six-year-old Marine Guilbert arrives at rehearsal with a shiny yellow vest peeking from her backpack, painted with the words “fiere d’etre un gilet jaune” (“proud to be a yellow vest”) and butterflies. Guilbert, a cleaner earning less than €1,000 a month, says she feels abandoned by the state and depends on family transfers and charity. She channels her frustration into theater: “We were born artists,” she declares.

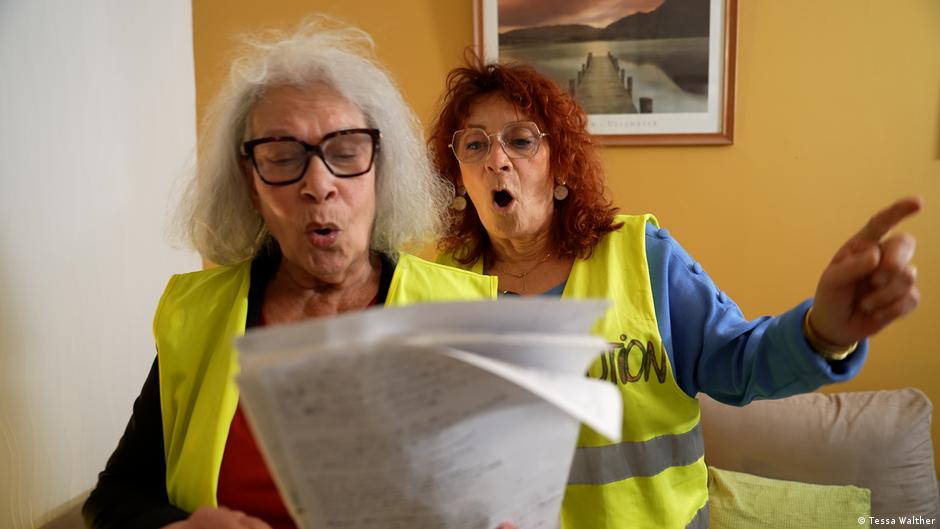

The group was founded by Anne-Sophie Bastin, a lawyer and former yellow vest from Lille. Disturbed by the violence and police clashes seen during the protests — clashes that Mediapart records linked to four deaths and hundreds of injuries — Bastin wanted to reflect those experiences on stage. She writes the scripts and directs the troupe. Their first performance in 2019 focused on the yellow vests; their new piece, set to be staged in late November in a 400-seat theater in Wasquehal, centers on Bobby Sands, the Irish Republican who died on hunger strike in 1981 — a figure Bastin finds inspiring.

On stage, former protesters confront a different dynamic: a leaderless movement accustomed to no hierarchy now follows a director. Bastin sometimes intervenes when actors improvise, reminding them, “It is me who wrote this script.” The troupe once numbered about 40 when it was limited to yellow vest members; it later opened to friends and family and now counts 15 people.

Beyond the hall, France faces ongoing social and political turmoil. A newer movement, “bloquons tout” (“let’s block everything”), has recently taken attention as the country wrestles with crises. A mid-October Le Monde survey found 96% of respondents unhappy with the state of the country. Analysts point to structural problems: growing inequality, persistent poverty, and a political system seen as unable to address them. Julien Talpin, a political scientist at the University of Lille, says anger is being expressed in nontraditional ways because the system no longer manages inequalities.

Government instability compounds matters. President Emmanuel Macron lacks strong parliamentary support to implement reforms aimed at tackling France’s economic issues. National debt exceeds 100% of annual income, and past attempts to curb deficits — including pension reforms and proposals to cut holidays — have met public backlash. France’s Inequality Observatory has reported a rising poverty rate over two decades. Experts warn that removing Macron might not resolve underlying problems and could open the door to the far-right National Rally.

In the Lille rehearsal room, many troupe members say they want Macron to resign, though some doubt any change in leadership would alter their lives. Pensioner Yolaine Jean Pierre, who composes protest songs, wears a badge with a yellow vest and a red heart. When she sings, the others join in; the songs target President Macron and express shared grievances. Jean Pierre says of the troupe, “We fight the same fight… We think the same. There is unity.”

For Guilbert, the stage is a place to be heard. “I hope our voice is being heard on the ground and on the stage,” she says, turning protest into performance and community.