In March 1938, SA paramilitaries marched through Vienna to celebrate Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria. When two SA men hung a sign reading “I am a Jewish pig” around an old woman’s neck, a man pushed through the crowd to help her. He was beaten, arrested and jailed — but freed quickly because of his name: Albert Göring, the younger brother of Hermann Göring, Hitler’s close confidant and commander of the Luftwaffe. Unlike Hermann, Albert actively opposed the Nazis.

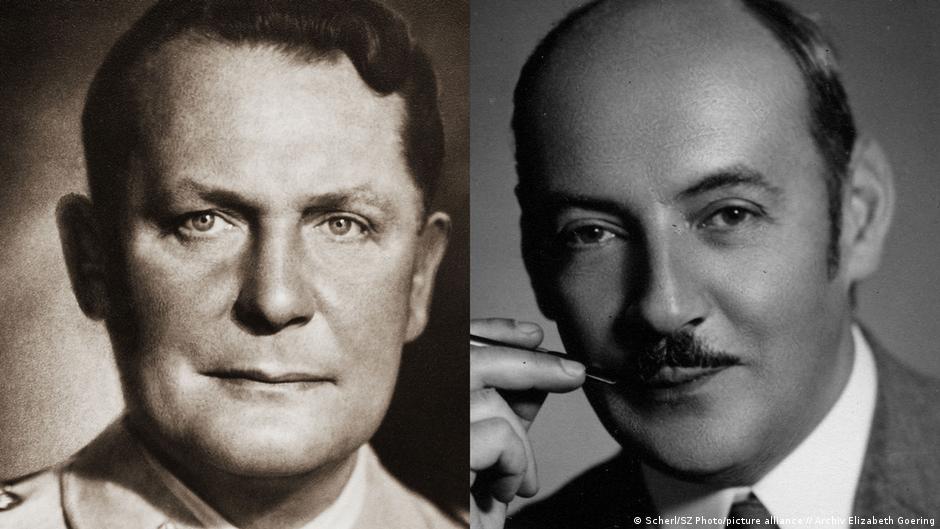

Hermann and Albert could not have been more different. Hermann was power-hungry, narcissistic and an early supporter of Hitler; Albert was a mechanical engineer turned film-industry technical director in Vienna who rejected Nazi ideology and brutality. Albert had no political ambitions; he was described as a charming bon vivant who used his position and family connections to help people persecuted by the regime.

Albert’s interventions began in the film world. When the silent-era star Henny Porten lost work in Germany for refusing to abandon her Jewish husband, Hermann asked Albert to help secure her a role in Vienna. Later, when the Gestapo came for Oskar Pilzer, a Jewish film producer and Albert’s former boss, Albert accompanied Pilzer to the Italian border to ensure his escape. He also intervened for composer Franz Lehár by asking Hermann to register Lehár’s marriage as a “privileged mixed marriage,” protecting Lehár’s Jewish wife from deportation.

Albert forged documents, organized escape routes and provided money to those fleeing persecution. His surname opened doors and intimidated officials; his family connection repeatedly proved useful. In 1939 he became export director at the Škoda Works in Brno, then under German occupation. The Czechs reportedly saw his appointment as a potential safeguard, believing someone with a line to a powerful relative in Berlin might protect their interests.

At Škoda, Albert passed on secret information to the Czech resistance — locations of military facilities and plans — drawing on business contacts and access tied to his position and family. Eyewitnesses said he arranged for prisoners from Theresienstadt to be taken to Škoda for “war-essential” work and then allowed to escape from trucks stopped in a forest. Such actions put him squarely in the Gestapo’s sights; he was declared an enemy of the state. Yet Hermann repeatedly intervened to protect him. Even in October 1944, when Hermann’s power was waning, he risked his standing to save Albert.

Hermann’s loyalty to family helps explain this protection. Biographers note a hierarchy in Hermann’s mind: himself first, then family, followed by the fatherland, Nazism and Hitler. Albert was both a headache and someone Hermann felt he could not sacrifice.

After the Third Reich fell, both brothers were detained. Albert refused to denounce Hermann during interrogations and spoke of his brother’s “warm-heartedness.” American investigators were skeptical; the Göring name that had enabled Albert to save lives also branded him a suspect. US investigator Paul Kubala dismissed Albert’s testimony as self-justification. Albert maintained a list of 34 names — people he said he had saved “at my own risk (three Gestapo arrest warrants!).” That list included notable figures, but no systematic search for those he named was ever undertaken.

A change of interrogators aided Albert’s fate. Victor Parker, who took over his case, was the nephew of Sophie Lehár, one of Albert’s beneficiaries. Hermann Göring committed suicide the night before his scheduled execution; Albert was released. Despite his release, Albert became a pariah in postwar Germany because of his surname. He could not find work as an engineer and survived by doing odd jobs and translations. Ostracized and socially shunned, he died in 1966 at 71.

Australian researcher William Hastings Burke became fascinated with Albert’s story after seeing a TV report. Burke spent years in archives, interviewing associates and relatives of those Albert helped, and published the book Thirty Four: The Key to Göring’s Last Secret. Burke describes Albert as a man who quietly stood up to the regime without seeking fame and argues that Albert’s example remains a powerful example of preserved humanity. Burke has nominated Albert Göring for recognition as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem.

Albert Göring’s life illustrates a stark moral divergence within one family: one brother deeply enmeshed in Nazi power, the other using his name and position to undermine it and save lives, often at great personal risk. This article was originally written in German.